A month ago we introduced Peekr, Scalock’s free security scanner for container images.

Peekr employs both static as well as dynamic scanning techniques. In today’s post we’ll discuss the importance and value of static scanning, i.e., scanning for known vulnerabilities.

The Known Knowns

A big part of any organization’s risk assessment process is to be aware of and gain visibility into vulnerabilities in the software being used. Those vulnerabilities can be categorized into two buckets - known and unknown. Unknown vulnerabilities, or zero-days, cannot be simply detected because, well, they are unknown. There are counter-measures, preventive and reactive, that an organization can take against those ‘known unknowns’, and we will address them in future posts.

But what about the ‘known knowns’? From an attacker point of view, having known vulnerabilities is akin to leaving the organization’s doors and windows wide open. Vulnerability scans are there to ensure that no such doors or windows are left open by mistake. We want to make sure that would-be intruders would have to work really hard to find a way in, or in other words minimize the threat surface as much as possible.

Rummy wasn’t talking about software vulnerabilities, but it’s a great quote and I had to use it

Docker and similar container technologies have made it easy and straightforward to download and use containers, bringing many advantages to application development and delivery including plug-and-play capabilities, rapid deployment, and transportability. These same advantages have lead to the proliferation of ready-to-use container images available in public registries. Organizations can deploy almost any software imaginable in a matter of seconds. But can they be sure that the image they are about to use is free of known vulnerabilities? It would be a mistake to consider images marked as ‘Trusted’ or ‘Official’ as being free of vulnerabilities. Those designations are only meant to reassure users that the images are authentic, official releases -- i.e. that their origins are vetted -- and not that they are vulnerability-free. New vulnerabilities are found every day, making existing and potentially in-use images much riskier.

Images built in-house are not necessarily better than those pulled from a public registry. It’s not realistic to expect that a developer would be able to make sure that no vulnerable components are used. The complexity is too great. Developers are delivery-oriented and often install the elements that they need without being fully aware of the risks they are introducing. Plus, of course, as images become older and new vulnerabilities are found in their components, the risk increases over time.

We recommend that organizations employ image scanning as built-in step in the development, deployment and production cycles of containers, and more so, it must be repeated periodically - to address both changes in images as well as newly discovered vulnerabilities.

Organizations that do so will benefit from:

- Risk assessment process that is based on complete information.

- Reduction to a minimum of the risk of components with known vulnerabilities being integrated or in use within their product or infrastructure.

- The quick exposure of relevant, recently published vulnerabilities. This minimizes the time window of increased risk that exists from the time that new vulnerabilities are published and until they are mitigated.

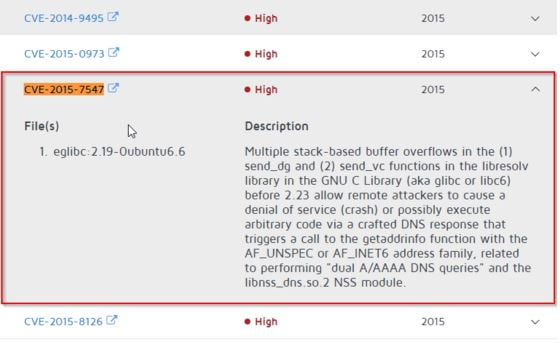

To show the importance of last bullet, just think about the recent CVE-2015-7547.

It was found that the glibc DNS client-side resolver is vulnerable to a stack-based buffer overflow when getaddrinfo function is used. A remote, unauthenticated, attacker could send a DNS responses to vulnerable application, crafting a DNS response to cause a stack-based buffer overflow, which could crash the application, cause DoS, or possibly run arbitrary code on behalf of application and with its permissions.

The core of vulnerability is that set size, 2048 bytes in this case, stack allocated space is mistakenly used instead of heap space, allocated for bigger buffers. The end result is stack overrun, hence stack-based buffer overflow. Here is a published proof of concept.

The glibc is a GNU C standard library and as such very widely used. The vulnerability exists in all versions 2.9 and up, since 2008 (!). Almost any Linux system is using glibc and getaddrinfo. Any containerised application using vulnerable version of glibc or based on images using such version of glibc library are vulnerable. You can see Docker's issue open on this vulnerability to get an idea.

Organizations using Peekr gain full visibility into which among their containers are vulnerable within days of publication, enabling a timely and well-informed remediation. Visibility is a key element in the ability to assess risk and build an effective remediation and patching plan.